The following excerpts are from recent readings of trauma:Domestic violence is control by one partner over another in a dating, marital or live-in relationship. Domestic violence includes physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological abuse, and abuse to property and pets. Exposure to this form of violence has considerable potential to be perceived as life-threatening by those victimized and can leave them with a sense of vulnerability, helplessness, and in extreme cases, horror. Physical abuse refers to any behavior that involves the intentional use of force against the body of another person that risks physical injury, harm, and/or pain.

Physical abuse includes pushing, hitting, slapping, choking, using an object to hit, twisting of a body part, forcing the ingestion of an unwanted substance, and use of a weapon.

Sexual abuse is defined as any unwanted sexual intimacy forced on one individual by another. It may include oral, anal, or vaginal stimulation or penetration, forced nudity, forced exposure to sexually explicit material or activity, or any other unwanted sexual activity.

Compliance may be obtained through actual or threatened physical force or through some other form of coercion. Psychological abuse may include derogatory statements or threats of further abuse (e.g., threats of being killed by another individual). It may also involve isolation, economic threats, and emotional abuse. Survivors face many obstacles in trying to end the abuse in their lives. The victim may face psychological and economic entrapment, physical isolation and lack of social support, religious and cultural values, fear of social judgment, threats and intimidation over custody or separation, immigration status or disabilities and lack of viable alternatives.

Abusers often starts insidiously and may be difficult to recognize. Early on, a partner may seem attentive, generous and protective in ways that later turn out to be frightening and controlling. Initially the abuse is isolated incidents for which the partner expresses remorse and promises never to do again or rationalizes as being due to stress or caused by something you did or didn’t do.

Traumatic stress is produced by exposure to events that are so extreme or severe and threatening, that they demand extraordinary coping efforts. Such events are often unpredicted and uncontrollable. They overwhelm a person's sense of safety and security. Terr (1991) has described "Type I" and "Type II" traumatic events. Traumatic exposure may take the form of single, short-term event (e.g., rape, assault, severe beating) and can be referred to as "Type I" trauma. Traumatic events can also involve repeated or prolonged exposure (e.g., chronic victimization such as child sexual abuse, battering); this is referred to as "Type II" trauma. Research suggests that this latter form of exposure tends to have greater impact on the individual's functioning. Domestic violence is typically ongoing and therefore, may fit the criteria for a Type II traumatic event.

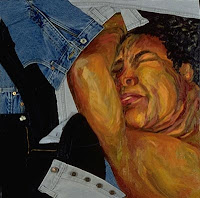

Violence causes invisibile wounds. Society does not appreciate the full range of human experience that exists alongside tragic events. Many traumatized people suffer a divide in their conscious minds. The mind stuggles to maintain its sanity by cracking in two: one half holding on to all it previously believed in, and the other half turning toward the chaos of anniilation. The

victim suffers the excruciating pain of trying to survive with both minds intact, the mind of 'hope' struggling to avoid dominance by the mind of 'despair.' This struggle continues long after the trauma has subsided.

When oppressed, people are capable of detaching their emotions and thoughts from their physical body. They can withdraw into themselves so that they 'saw nothing, heard nothing, and spoke nothing.' They can behave like ragdolls, having no reaction to what occurs around them.

Many victims of trauma, when asked how they feel at a particular time, describe feelings of emptiness or being numb. Some victims have difficulty showing emotion, or identifying their emotion. They may appear like a blank slate, or they may constantly hide behind a smile as a way to shield others from sensing their despair. Often, victims of trauma have difficulty reacting to the trauma of others. They are able to survive day to day by being great pretenders.

Responses to traumatic experiences can be divided into at least four categories (Meichenbaum, 1994).

Emotional responses include shock, terror, guilt, horror, irritability, anxiety, hostility, and depression.

Cognitive responses are reflected in significant concentration impairment, confusion, self-blame, intrusive thoughts about the traumatic experience(s) (also referred to as flashbacks), lowered self-efficacy, fears of losing control, and fear of reoccurrence of the trauma.

Biologically-based responses involve sleep disturbance (i.e., insomnia), nightmares, an exaggerated startle response, and psychosomatic symptoms.

Behavioral responses include avoidance, social withdrawal, interpersonal stress (decreased intimacy and lowered trust in others), and substance abuse. The process through which the individual has coped prior to the trauma is arrested; consequently, a sense of helplessness is often maintained (Foy, 1992).

Domestic violence leaves the injured feeling that they deserved their punishment.

Sexual assault leaves the injured feeling that they are unclean and need to be cleansed.

Violence's major message: "You are nothing. You are worthless."

Oppression places the victim in a position of no control over their body, over their environment. This may result in obessive-compulsive types of behaviour as a way to regain control over their environment. They may exhibit symptoms of eating disorders, or the need to constantly structure their environment and lifestyle. They may chronically clean (their body or their environment), organize, or make lists. They make seek routine as a way of organizing or controlling their life. They may engage in self-harm activities, believing that they deserve punishment or as a way to reinforce the worthlessness that they were led to believe of themselves. This shows that violence does not end with the perpetrator but continues with the victim.

Perpetrators find ways of getting the victim to doubt their own sanity. Victims, in turn, doubt that anyone--even trained health professionals, police, or the justice system--would believe in the truthfulness of their experience. History shows that

victims are trapped in a vicious  cycle whereby they are abused twice over--once by their perpetrators and then by the very people they turn to for help

cycle whereby they are abused twice over--once by their perpetrators and then by the very people they turn to for help--including policemen, judges, friends, and even relatives. Given that police have one of the highest rates of domestic violence and often do not receive adequate mental health/trauma training, it is understandable why they are not completely entrusted with the victim's experience.

It is common in abuse situations for victims to question their own reality. They develop a hard shell or dummy personality so that they can emotionally resist all that is happening to them. Some victims even have difficulty breaking communication with those that caused them harm. Many victims cannot even tell their parents, relatives, friends, coworkers, or neighbours about the abuse because of shame and humiliation, particularly in cases of low-grade chronic violence seen in situations of domestic abuse. In these situations, it is difficult for society to understand why victims remain in their situations, not realizing the brain-washing that occurs to convince the victim that it's their fault, it's for their own good, no one will believe them, or they are over-exaggerating. The victim then enters the perpetrator's reality, meaning that the abuse was normal and to be accepted. This may result in cognitive dissonance, which is the ability of the victim to simultaneously hold at least two opinions or beliefs that are logically or psychologically inconsistent. In some cases the person is aware of the contradiction. In other cases they are only conscious of the two beliefs separately, in different contexts. Also, people feel cognitive dissonance when they have performed actions that are inconsistent with their conscious beliefs. People who feel dissonance tend to try to reduce the dissonance by changing either one of their beliefs or their actions, such as victims convincing themselves that their abusers truly care about their wellbeing or victims believing that they instigated a rape. Contrary to untested popular belief,

trauma survivors experiencing cognitive dissonance may engage in self-sabotaging behavior, but not suffer from low self-esteem.

Domestic violence often becomes a pattern made up of three stages depicting how love (for the partner), hope (that the relationship will get better), and fear (of retaliation for ending the relationship) keep the cycle in motion and make it hard to end a violent relationship. Perpetrators of violence often apologize, make promises to change, and pay special attention to their partners immediately following a violent incident. This period is sometimes referred to as the "honeymoon period" because of the positive feelings resulting from the release of tension and the hope that things will change for the better. This kind of spontaneous change rarely occurs, however, because the underlying pattern of control and lack of communication and compromise has not changed.

Every abusive person has a different set of signs that indirectly tells the partner an attack is about to happen. Examples may include unstable employment, pregnancy, and financial difficulty. Being aware of these “signs” can help a woman in an abusive relationship know when she will be attacked. Society also has not acknowledged the

pattern of escalating danger to the victim when divorce or separation is sought.

It takes a victim a lifetime to clean off the defilement of a single act of rape or years of domestic abuse. Humiliation is closely associate with the feelings of shame, embarrassment, disgrace, and depreciation that are common reactions to violent actions.

Victims may refuse to speak or only say what they think others--including police or loved ones--want to hear. When they choose to carefully share their story with someone of trust, they frequently

share  only a fraction of the their pain

only a fraction of the their pain. They are vulnerable to emotional and physical pain when they retell their stories. They may hesitate to relate an event for fear that a fresh wave of suffering will surface and they will be reijured. Often they have gained significant insights that are barely holding them together. Some victims may be eager to share their story in order to heal, but cannot find a person of trust to divulge to. Others may not want to share how they are coping, lest doing so will make their strategies fail.

Sufferers do not suffer all the time. There are lapses when they can experience laughter, but ask them if they are truly happy and they may not be able to identify with that emotion. For a survivor to feel free to experience their emotions, they must be assured a safe forum. Like the majority of humans, trauma survivors want to feel loved and safe to love.

Traumatic events can be associated with positive changes in an individual's personality and behaviour. Many survivors choose to take the lessons learned from their personal experiences of violence to make positive contributions to society. They may provide direct assistance to other trauma victims, or get involved in activities that provide relief of suffering to others, humans and animals alike. Traumatized persons are not usually emotionally hardened by violence but are, in contrast, delicately attuned to the nuances of human interactions. They are extremely sensitive and empathetic to the plight of others.

Formulating new relationships is very difficult for survivors of trauma. Encounters with others open up the possibility of the unknown, particularly disappointment. There is a risk that the other person may not want to be intimately involved with someone who has survived trauma. Survivors experience this rejection as being revictimized--judged for experiences over which they had little control. Victims intensely fear rejection or that no one will have interest in their story. Telling their story is the centerpeice of the healing process, told in their words about the traumatic life events they have experienced and the impact of these events on their wellbeing.

References

Dutton, M.A. (1994). Post-traumatic therapy with domestic violence survivors. In M.B. Williams & J.F. Sommer (Eds.), Handbook of post-traumatic therapy (pp. 146-161). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Dutton, M.A. (1992). Women's response to battering: Assessment and intervention. New York: Springer.

Foy, D.W. (1992). Introduction and description of the disorder. In D. W. Foy (Ed.), Treating PTSD: Cognitive-Behavioral strategies (pp 1-12). New York: Guilford.

Ganley, A. (1989). Integrating feminist and social learning analyses of aggression: Creating multiple models for intervention with men who battered. In P. Caesar & L. Hamberger (Eds.), Treating men who batter (pp. 196-235). New York: Springer.

Graham-Bermann, S. (1994). Preventing domestic violence. University of Michigan research information index. UM-Research-WEB@umich.edu.

McKay, M. (1994). The link between domestic violence and child abuse: Assessment and treatment considerations. Child Welfare League of America, 73, 29-39.

Meichenbaum, D. (1994). A clinical handbook/practical therapist manual for assessing and treating adults with post-traumatic stress disorder. Ontario, Canada: Institute Press.

Schwarz, R. (2002). Tools For Transforming Trauma. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Van der Kolk, B. A., McFarlane, A. C. & Weisaeth, L., Editors. (1996). Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. New York: The Guilford Press.